Physics Meets Physiology: Using Quantum Tech to Solve Iron Disorders

Science Victoria Edition

Founder and CEO, FeBI Technologies

Iron helps our bodies build the red blood cells that transport oxygen to our muscles for energy production. It also supports energy metabolism, cognitive function, and a healthy immune system.

But having too much or too little iron causes health problems. Managing such iron imbalances demands quick and accurate measurement. That’s what FeBI Technologies is all about.

Iron Disorders Today

Too little iron, iron deficiency, affects more than 2 billion people worldwide, making it the leading nutrient deficiency.1 Infants and young children, premenopausal and pregnant women, and older people are particularly at risk. Women are more likely to be affected than men, because of the high iron demands of menstruation, pregnancy, and breastfeeding. In Australia, an estimated 1 in 5 women are iron deficient compared to 1 in 20 men.

The body’s ability to produce red blood cells decreases with low iron levels, and this reduces oxygen transport and leaves us feeling both physically and mentally exhausted. Low iron levels also slow the production of immune cells which can significantly reduce immune responses, leaving us prone to infections, delaying recovery from illness, and hastening the progression of chronic conditions (such as chronic kidney disease).

Iron deficiency can be treated, and in some instances prevented, using either iron tablets or an intravenous iron infusion. But ensuring appropriate diagnosis of iron deficiency, and subsequent management or prevention, requires accurate measurement of the body’s iron stores.

At the other end of the spectrum, having too much iron, iron overload, also causes health problems. Hereditary haemochromatosis is Australia’s most common genetic disorder, affecting about 1 in 200 people of European descent.2 Too much iron is absorbed and stored leading to fatigue and shortness of breath and the accumulation of excess iron in the liver and heart.

This accumulation of iron can lead to significant organ damage. So patients must undergo frequent sessions of blood removal to reduce their overall iron levels. To do this safely we need tests that can accurately tell us when enough blood, and iron, has been removed to ensure that the treatment is not pushing people towards iron deficiency.3,4

Testing for Iron Deficiency and Overload

Iron deficiency and iron overload share common symptoms, but demand very different treatments. So it is important for people with suspected iron imbalance to get an accurate diagnosis before beginning treatment. Accurate tests are also important for monitoring the response to treatment.

A bone marrow biopsy is the current clinical gold standard for assessing our iron stores; it is rarely prescribed, however, because it is invasive and expensive. So under normal circumstances iron status is assessed by measuring the blood serum levels of ferritin, the body’s primary iron storage protein. The iron load contained in ferritin can vary widely, from empty up to a theoretical capacity of about 3000 iron atoms per protein molecule.5 In healthy people, measures of serum ferritin protein correlate strongly with iron stores in bone marrow and it thus offers a cheap and effective measure of an individual’s iron levels.6

But unfortunately ferritin levels change in response to inflammation.7 This means that serum ferritin can increase independently of iron levels in conditions such as diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and cancer, as well as during viral infections such as cold and flu, and after injury or surgery. The consequence is misdiagnosis of iron disorders, particularly in people with chronic health conditions.

Rethinking The Challenge with Quantum Technology

To address such problems, we need to rethink monitoring iron levels to ensure tests are effective and affordable for all that need them. At FeBI Technologies – a company founded by iron researchers Gawain McColl and Nicole Jenkins from the Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health and physicists David Simpson and Liam Hall from the University of Melbourne – we think the answer lies in quantum technology.

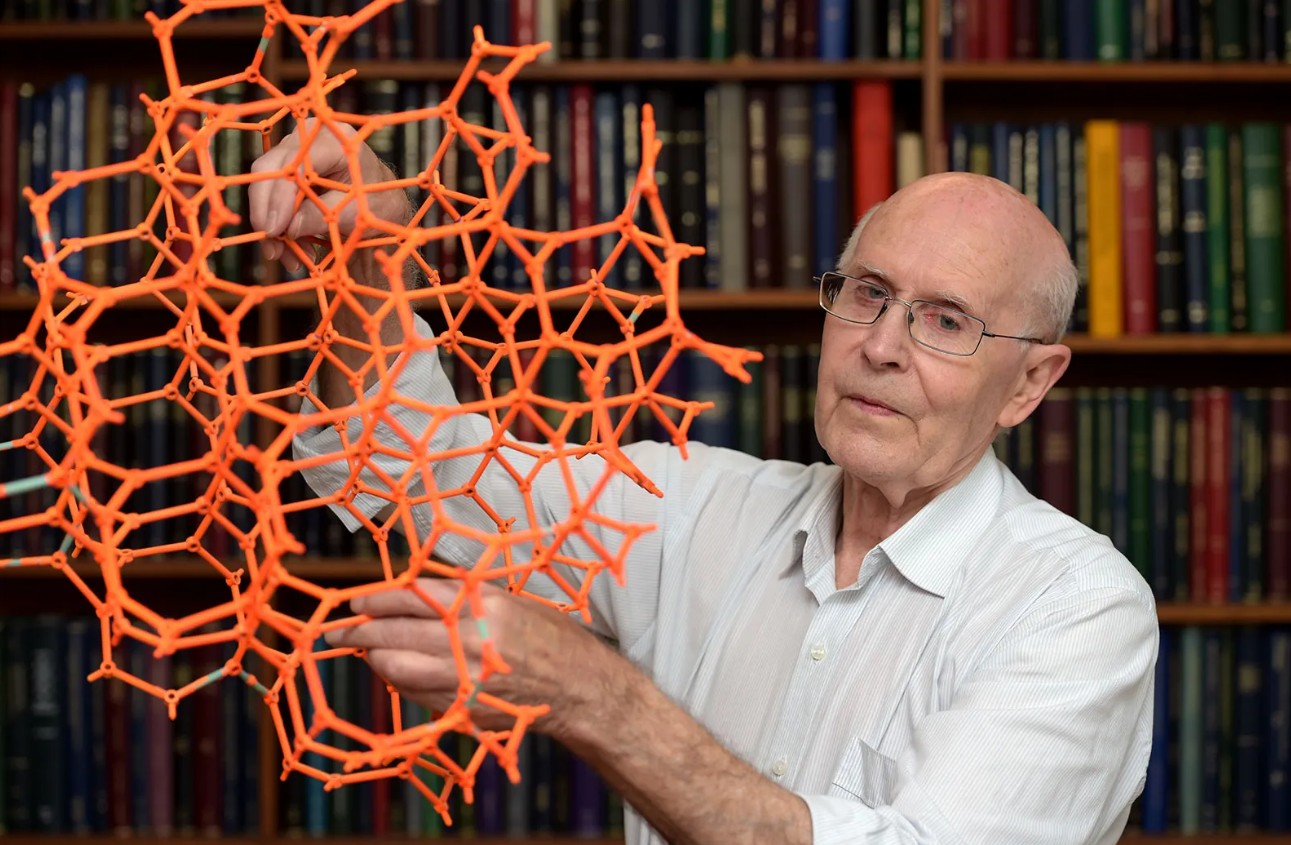

Our groundbreaking approach lies in using diamond-based quantum sensing technology. Rather than focusing on the ferritin protein, this allows us to measure the level of iron inside the ferritin, the Ferritin Bound Iron (FeBI).

One of the key breakthroughs in physics over the past decade has been the exploitation of quantum effects to provide enhanced sensitivity when compared to existing means of measurement. Our innovative system effectively performs an MRI on a nanoscale, allowing us to pick up the magnetic signature of the iron within ferritin. Before quantum sensing, this was not possible.

Our technology is, in a sense, a quantum counterpart of an MRI. In traditional MRI scanners the iron load can be determined by monitoring magnetic changes in the presence of ferritin. The FeBI quantum sensing technology functions via a similar operating principle, but our novel sensing technology is nine orders of magnitude more sensitive than traditional MRI and represents a transformative shift in direct iron detection.

Victoria's Growing Quantum Community

Being based in Victoria allows us to leverage significant local strengths in biomedical research and also take advantage of the growing quantum diamond community. Just this month, the world’s first quantum diamond foundry open in Notting Hill, near Monash University. Its establishment was supported by a $10 million investment from the Victorian Government’s venture capital arm, Breakthrough Victoria. A quantum diamond foundry is an advanced manufacturing facility where diamonds, created in a lab rather than mined, are then tuned and set within integrated circuits to provide computing and sensing electronics.

FeBI Technologies is also partnering with clinical haematologists, sports scientists, and First Nations health experts to test and validate its new measure of assessing iron status. The FeBI technology will enable monitoring of diseases where iron status is vital for health management such as chronic kidney disease and diabetes, which disproportionately affect First Nations people.

Members of the development team are currently in Katherine in the Northern Territory gathering real-world data to assist in the design of a blood-test device for iron levels which will operate in a range of environments.

Importantly, we are focused on translating our technology to establish a better test for iron status that is both accurate and affordable, so that it can be widely available.

References

- Assessing the iron status of populations : including literature reviews: report of a Joint World Health Organization/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Technical Consultation on the Assessment of Iron Status at the Population Level, Geneva, Switzerland, 6–8 April 2004. – 2nd ed., (2004). https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/6681

- Olynyk, J. K. et al. (1999) A population-based study of the clinical expression of the hemochromatosis gene. The New England Journal of Medicine 341: 718-724. doi:10.1056/NEJM199909023411002

- Infanti, L. et al. (2024) Blood donation for iron removal in individuals with HFE mutations: study of efficacy and safety and short review on hemochromatosis and blood donation. Frontiers of Medicine (Lausanne) 11: 1362941. doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2024.1362941

- Barton, J. C. & Bottomley, S. S. (2000) Iron deficiency due to excessive therapeutic phlebotomy in hemochromatosis. American Journal of Hematology 65: 223-226. doi: 10.1002/1096-8652(200011)65:3<223::aid-ajh8>3.0.co;2-9

- Hagen, W. R. (2022) Maximum iron loading of ferritin: half a century of sustained citation distortion. Metallomics 14. doi.org/10.1093/mtomcs/mfac063

- WHO guidelines on use of ferritin concentrations to assess iron status in individuals and populations. (2020) Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Wang, W. et al. (2010) Serum ferritin: Past, present and future. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1800: 760-769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagen.2010.03.011

Discover how you can join the society

Join The Royal Society of Victoria. From expert panels to unique events, we're your go-to for scientific engagement. Let's create something amazing.