More Power, Lower Environmental Cost: How Victorian Innovation could dethrone the Lithium-Ion Battery

Science Victoria Edition

Director, ARC Research Hub on Advanced Manufacturing with Two-Dimensional Materials (AM2D), Monash University

Think about your day.

You wake up, check your phone, clean your teeth, travel to work in an electric or hybrid bus or car, use a laptop or tablet, and come home and employ multiple remotes to control household appliances before bedtime.

What do all these things have in common?

Batteries.

The invisible engines of modern life

Batteries store energy, and release it on demand when we need it. Without them, most of our technology, from phones to electric vehicles, simply would not work. And their uses are expanding. Many think that future, lightweight powerful rechargeable batteries will soon be powering drones and even aircraft in the future.

Right now, the one battery that rules them all is the lithium-ion battery, Li-ion for short. These batteries move tiny lithium ions back and forth between two electrodes, a lithium-rich cathode and a graphite anode, as they charge and discharge. They’re reliable, affordable, and can store a lot of energy for their weight holding about 250 watt-hours per kilogram.

But there’s a problem. The materials used in constructing these batteries—such as cobalt, nickel, and manganese—are becoming harder to find. Most of the world’s supply comes from only a few regions, and demand is growing fast. This creates supply-chain problems and makes some countries dependent on others for their energy technology.

So scientists are asking: Can we make batteries from materials that are easier to find and better for the planet?

The Lithium-Sulphur Battery

One exciting answer is the lithium–sulphur (Li–S) battery. Instead of using rare metals, Li–S batteries are made from lithium, carbon, and sulphur. These are common and inexpensive materials. In fact, much of the material required for the battery can be recovered from waste streams – sulfur from petroleum refining, for example, and lithium extracted from tailings and leachates at Australia’s spodumene mining operations. So, if we could mass-produce such batteries, we’d have a product that is not only cheaper, but also more environmentally and globally fair.

Twice the energy or half the weight

Even better, Li–S batteries can store at least twice as much energy as today’s Li-ion cells, 500 watt-hours of energy per kilogram or more. That means lighter batteries for powering electric aircraft, phones that last for days without charging, and cheaper storage for solar and wind power.

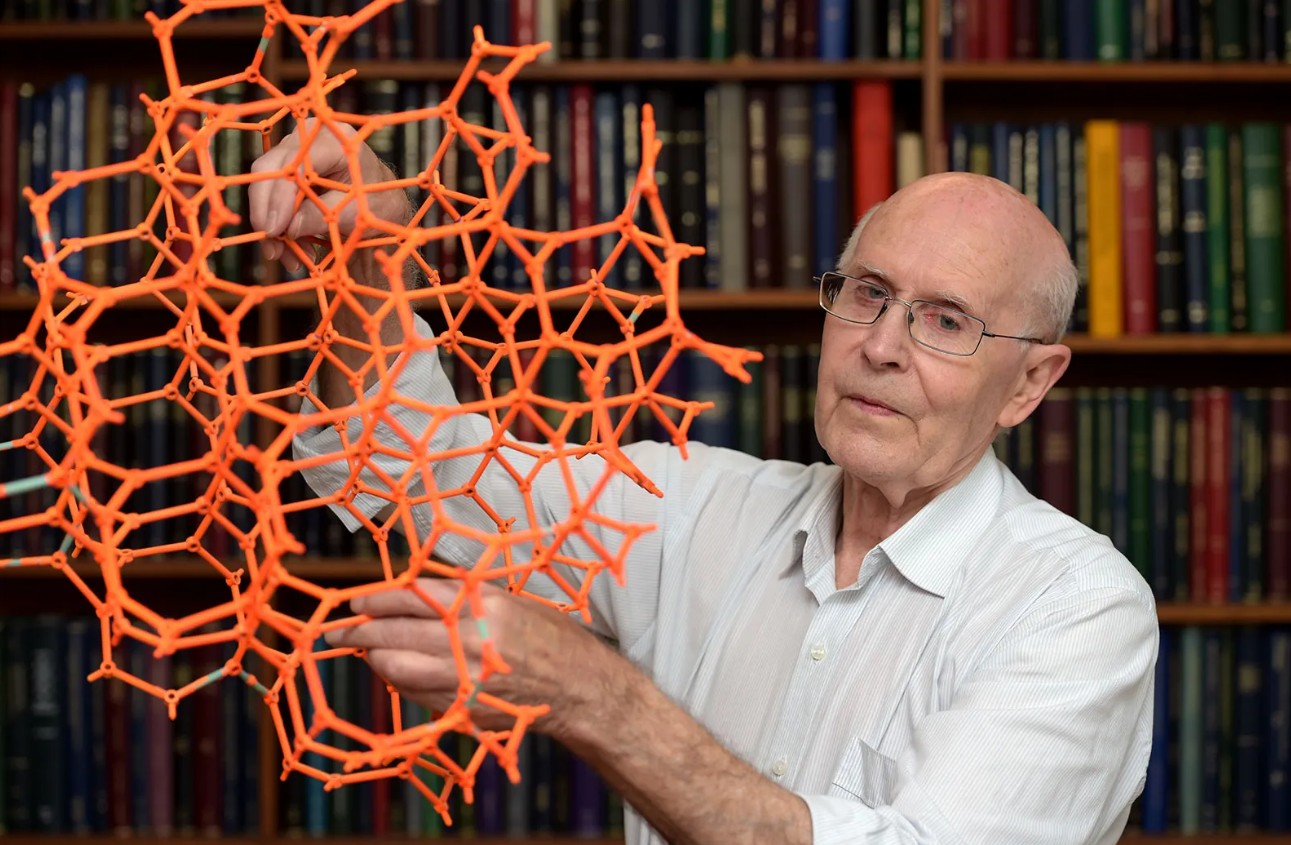

Of course, every new technology has its challenges. Li–S batteries can be slow to charge and tend to degrade, losing their capacity over time. But a team of researchers at Monash University has been working for more than 10 years to solve these problems using readily affordable off-the-shelf materials.

They have used the chemistry of the well-known and inexpensive household antiseptic betadine. It not only stops the degradation, but also opens up the structure of the electrodes to allow rapid charging and discharging. The developers have already built working prototypes to prove it can be done.

.jpg)

The work of the Monash team has been supported in part by the US Air Force Office of Sponsored Research, which is a testament to international recognition of their expertise.

Commercialisation

From this research, a new Victorian company called Ghove Energy has emerged, and is currently raising pre-seed funding and inviting investors to join their venture. The scientists behind Ghove Energy want to bring Li–S batteries to market—using Australian resources, Australian innovation, and Australian manufacturing. With the global lithium-sulphur battery market expected to be worth more than $300 million by 2028, Australia is potentially at the forefront of a rapidly expanding industry, that has the potential to create jobs and drive economic growth.

The researchers know the competition is tough, but they’re determined to make a difference. So the team continues to innovate. Currently they are refining methods that reduce the amount of lithium needed, together with new additives, that promise to speed up charge and discharge times even more.

If they succeed, their batteries will not only power our devices, they might also help rebalance the world’s energy future.

Want to stay up to date and get articles like this and the latest Science Victoria digital magazine delivered straight to your inbox?

Subscribe for free now at subscribe.rsv.org.au

Discover how you can join the society

Join The Royal Society of Victoria. From expert panels to unique events, we're your go-to for scientific engagement. Let's create something amazing.