From Test Tubes to Nobel Prize: The Australian Material That Captures CO2

Science Victoria Edition

Professor of Materials Science and Engineering, Monash University

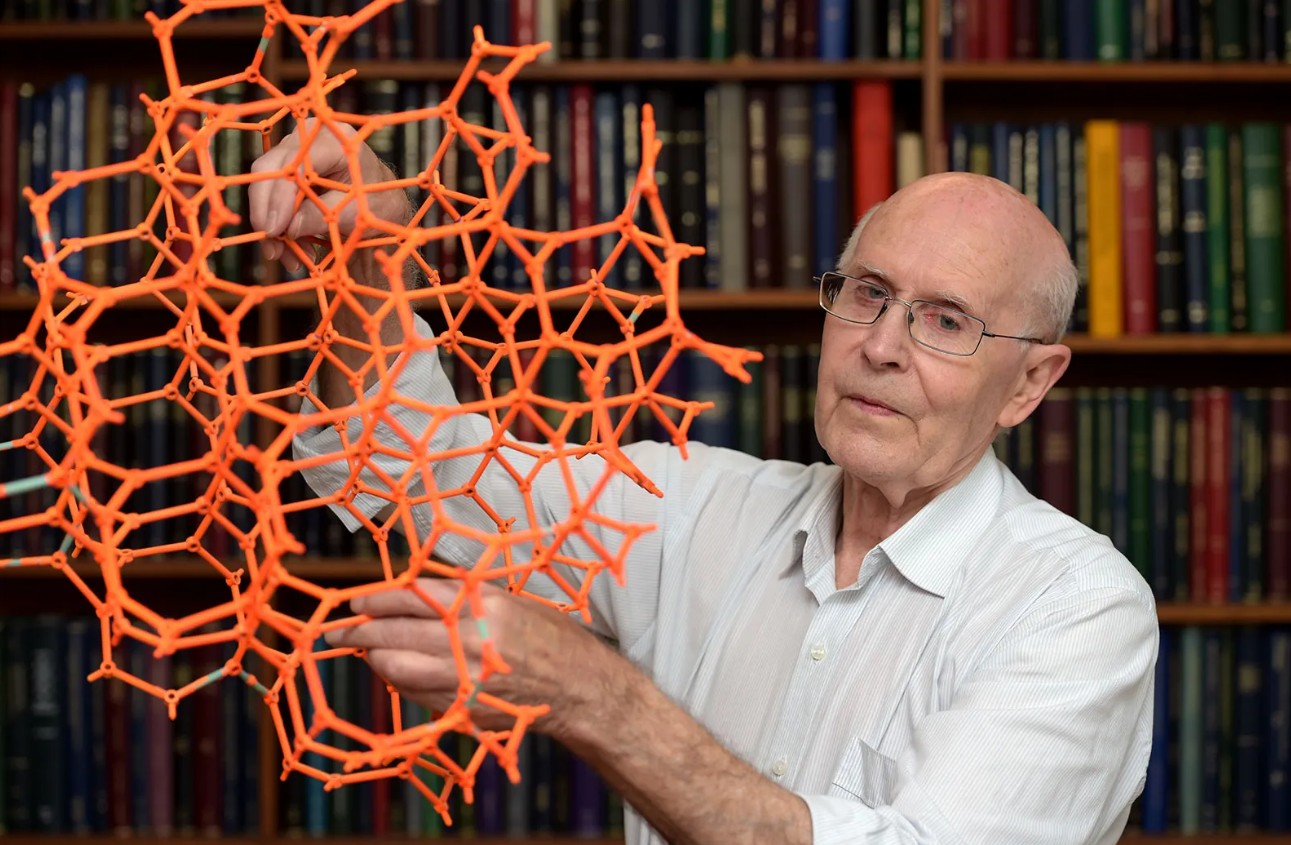

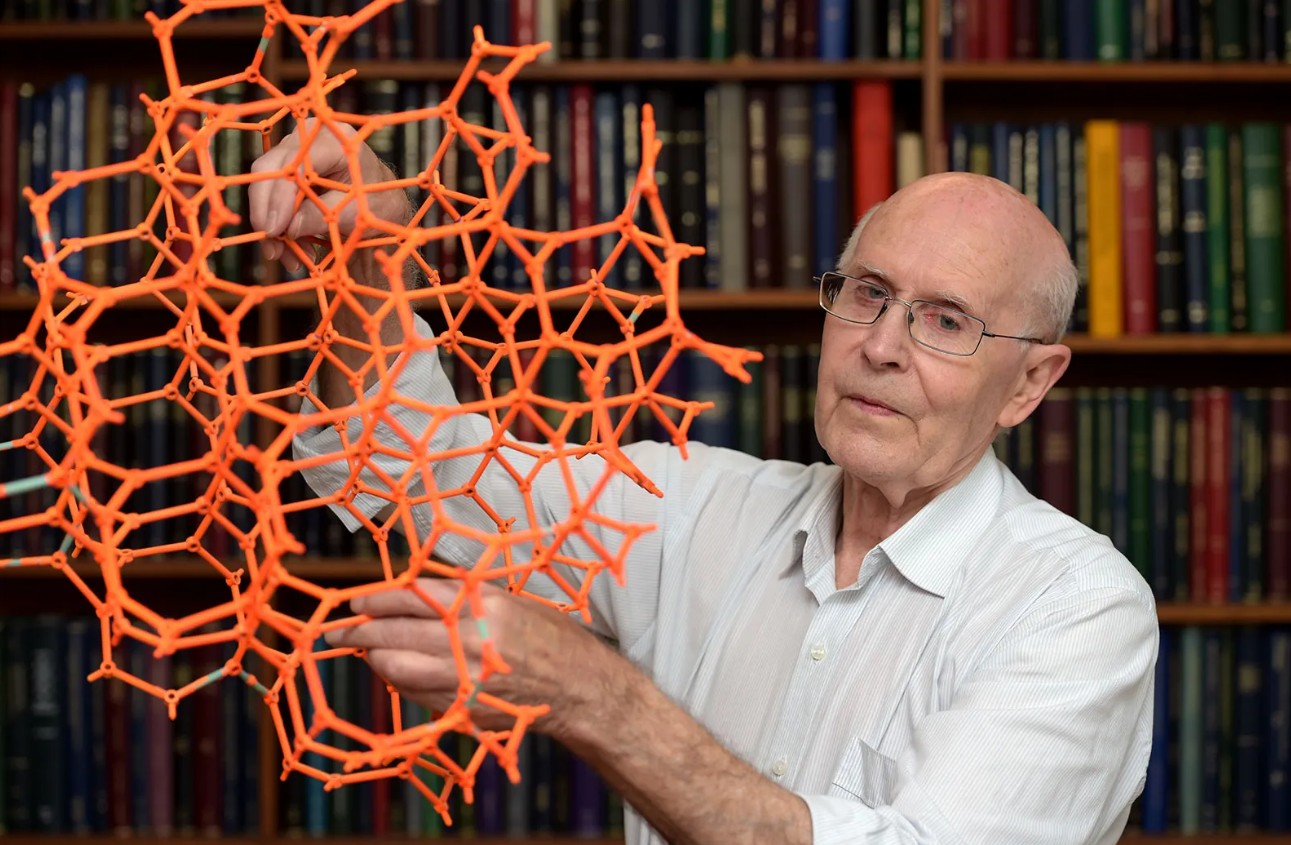

The awarding of the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry to Richard Robson is a major milestone for Australian science, particularly for Victoria. Over the decades, Professor Robson and other Australian researchers have played a key role in expanding the field of MOF applications.

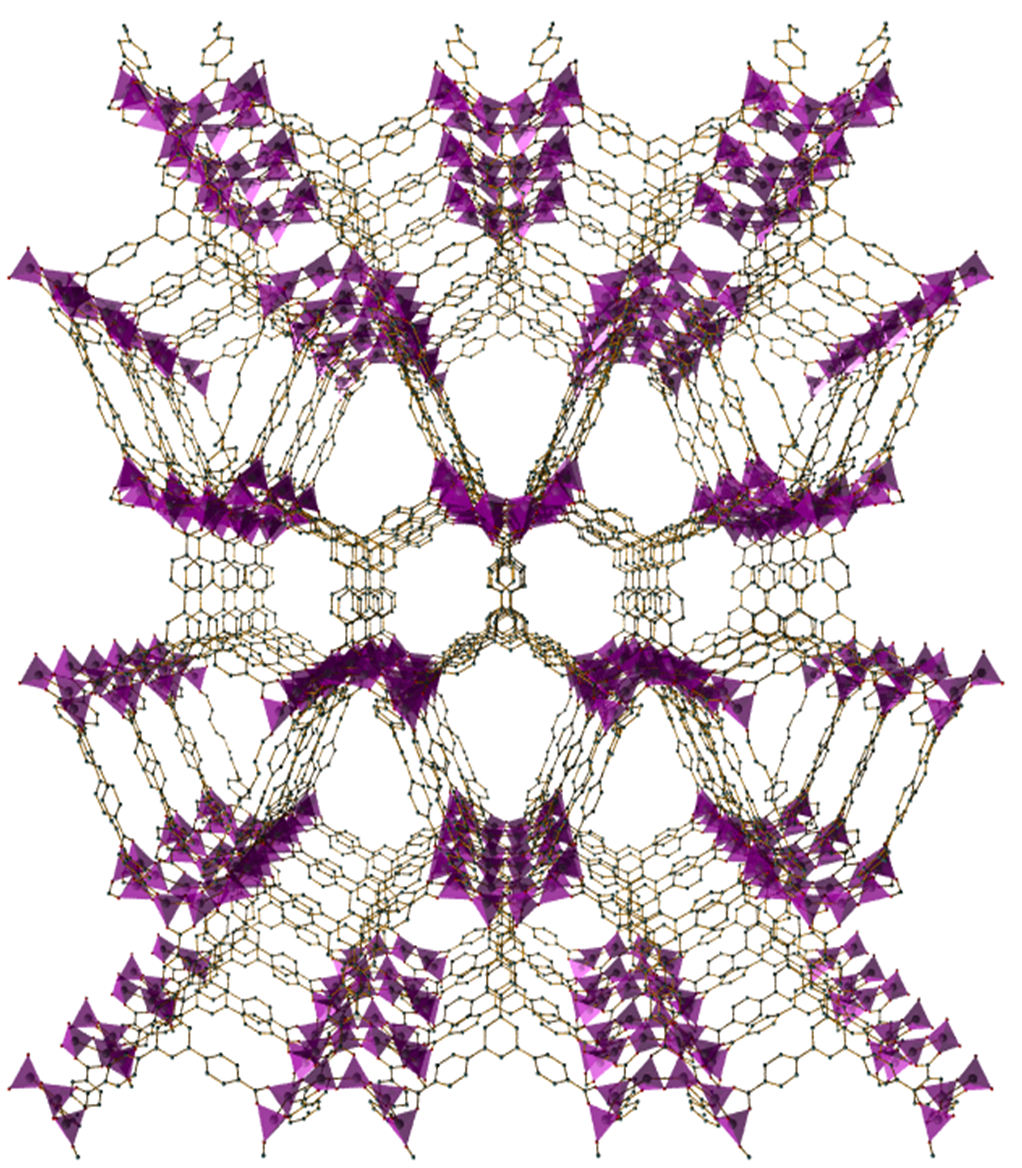

Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) are a family of more than 100 thousand materials. They are combinations of different metals joined to one another by organic linking molecules to form an extended framework structure, in which every atom is exposed on the inside of a pore.

MOFs are so porous that the surface area inside a few grams of material is the size of a football ground. What’s more, by changing the combination of metals and linker molecules, the properties of the size of the pore and the surface inside can be “tuned”.

MOFs - The Ultimate Separators

This tunability allows researchers to engineer a specific MOF to recognise or fit one particular molecule and no other. So that means that MOFs can act both as sieves and sponges at the same time, accepting one molecule and rejecting others.

They are the ultimate separators. For example, MOFs can be designed to capture CO2 molecules directly from the air, while repelling and rejecting more than 2000 other different molecules.

The journey from proof of concept to production

The first efforts in the field were simply “blue-sky” research, centred upon the proof-of-concept that such materials could exist. Many regard Richard Robson’s 1989 article entitled, Infinite Polymeric Frameworks Consisting of Three Dimensionally Linked Rod-like Segments as the first report in the field. In it, he famously predicted many of the forthcoming applications, although the first material he made was not stable enough to be utilised in any way.

But in work that soon followed, Robson’s two other Nobel-laureate colleagues, Susumu Kitagawa and Omar Yaghi, reported new MOFs that were stable enough to allow removal of a solvent trapped in the pores without collapsing the overall MOF structure itself. This allowed exploration of applications such as storing hydrogen. Even the very first reports of this showed record performances.

The early 2000s saw a rapid expansion of the field, and local groups led by Batten (Monash University), Kepert (University of Sydney) and Abrahams (University of Melbourne) were prolific in expanding the range of known MOF materials. New applications in separation, the catalysis of chemical reactions and in defence emerged during this period.

In 2010, a group of MOF researchers in Australia were awarded a nationwide grant from the Science and Industry Endowment Fund (SIEF) Foundation, to target the capture of CO2. The SIEF money allowed the MOF researchers to try some bigger and riskier concepts, and to build the strong teams needed to do great science in modern times. (SIEF was originally established in Australia in 1926 along with the predecessor to the CSIRO, but it has recently been rejuvenated by money from the CSIRO’s Wi-Fi patent.)

At this time the potential for commercial applications came to the fore. But in order to allow these new applications to be tested out at a pilot scale, researchers needed to be able to manufacture meaningful quantities of MOF without the cost being prohibitive. So a team from CSIRO and Monash University pioneered the use of continuous flow chemistry to make MOFs in minutes, as opposed to the typical 24 to 48 hours needed. This discovery was later licensed to Noble Park manufacturer Boron Molecular. These days, several manufacturers globally have developed MOF production methods and dozens of different MOFs are now available for purchase at scale.

The Growing Applications of MOFs

People often asked how much a MOF costs. That can be a difficult question to answer when you are talking about 100 thousand different materials. But prices can be as low as tens of dollars a kilo in some instances. It is in large part driven by the cost of the ingredients for a particular MOF.

With greater comfort around the ability to access MOFs, many applications have been under active development over the past decade.

The Chicago-based corporation Numat has been very successful in developing MOFs which store the toxic gases arsine and phosphine inside their pores. These gases are crucial in the semiconductor industry. By storing them inside MOFs, the transport of these dangerous gases has been made much safer.

California-based Mosaic Materials developed a MOF-based solution to capturing CO2 in low concentration environments. Similar efforts in Australia include Sydney-based AspiraDAC and the CSIRO’s Airthena, first announced in 2020 but with developments ongoing.

Nobel laureate Yaghi has been highly active in developing MOFs to pull water directly from air. He founded Atoco to further these interests. Here in Melbourne, Airvoda offers similar capabilities.

MOFs can also capture toxic gases to which defence force personnel, firefighters and police can be exposed. Brisbane-based EPE has taken the lead in developing these materials for use in a new respiratory canister.

MOFs have a role to play in the fields of green energy and extracting critical minerals, large industries which are emerging in our new economy. The extraction of lithium has been first cab off the rank, with several companies exploring MOFs to speed up the removal of lithium from brine, a process that can currently take years by slow evaporation.

The awarding of the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry to Richard Robson is a major milestone for Australian science, particularly for Victoria. Australian innovations in scalable production and commercialisation are helping to bring these materials out of the lab and onto the market.

Discover how you can join the society

Join The Royal Society of Victoria. From expert panels to unique events, we're your go-to for scientific engagement. Let's create something amazing.