The School Solar Vehicle Challenge

Science Victoria Edition

Chair, Victorian Model Solar Vehicle Challenge

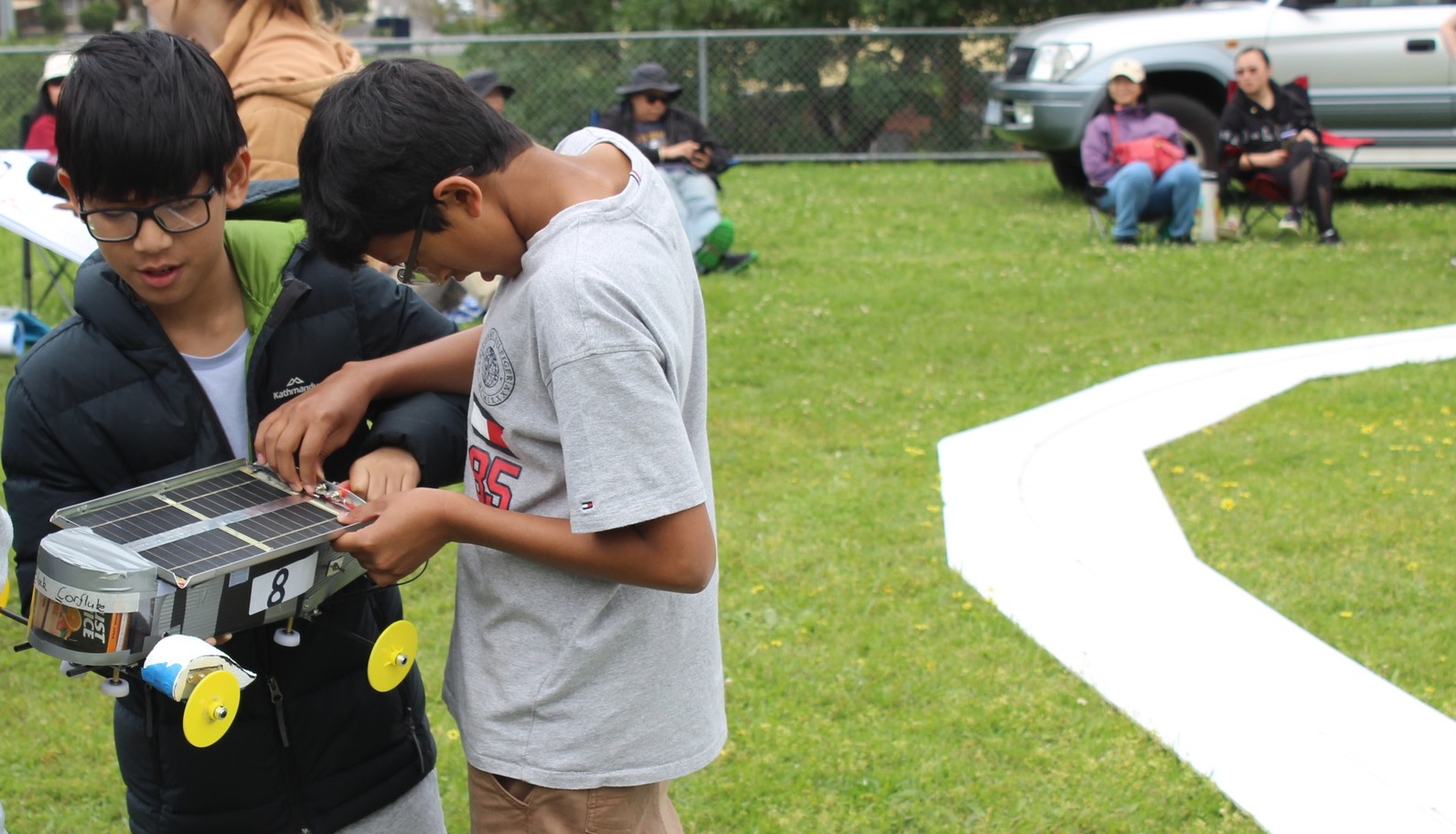

If you had to explain the Victorian Model Solar Vehicle Challenge at a backyard barbecue, it’s really quite simple: a competition where students design, build, and race their own model solar-powered vehicle, be it a car or a boat.

Now that might sound prosaic. But if you have ever stood on the sidelines and watched a child see their creation zoom forward, powered by nothing but the sun, you will know it is anything but. And there is a particular mix of disbelief and pride that crosses their faces—and sometimes those of their parents too.

“Wow, I didn’t think this could happen,” is a phrase organisers hear year after year.

A volunteer-driven tradition

The Victorian Challenge began in 1990 as a way to give students a taste of the excitement generated by the World Solar Challenge – where teams race solar cars from Darwin to Adelaide – but at a fraction of the cost and scale. The program has since spread to other states, and boats were added in 1994 to involve younger students. Today the Model Challenge continues as a not-for-profit program run entirely by volunteers.

Every year, hundreds of students across Victoria take part. Regional schools are often strongly represented, perhaps because of their build-it-yourself culture. Some of the participants go on to study engineering, medicine, or science. Others discover that their strengths lie in sponsorship or team organisation, later pursuing business degrees.

“I think the biggest challenge is simply convincing people that, yes, they can do this,” says Clint Steele, chair of the Victorian branch. “We have set things up so schools can get involved even if they know nothing at the start.”

More than classroom science

What sets the Challenge apart from ordinary science lessons is that it is not about worksheets or lab demonstrations. It is about building something real, testing it, and fixing it when it fails.

“Tell me and I forget, show me and I remember, involve me and I understand,” Clint reflects. “We see students who struggle in traditional classrooms suddenly thrive when they can work with their hands. For them, everything clicks.”

Educator and committee member Wendy Jobling agrees. She recalls primary students eagerly returning year after year, not because they were made to, but because they knew they could always improve their design. “It is that ongoing cycle of problem-solving that keeps them hooked,” she says.

Voices from the field

Parents play a key role. When Newport Lakes Primary in Melbourne’s western suburbs faced losing its program, parents Dave Child and Martin Foster stepped in. With little more than organisational skills and a willingness to give up some Sundays, they rallied students, secured a $1500 STEM grant, and even built a makeshift test pool from pallets and a tarpaulin.

“It is really no more onerous than organising a school fundraiser,” Martin laughs. “If you build the structure, volunteers with specialist skills will magically appear.”

Teachers also find unexpected support. At Kingsville Primary, also in the west, parent Adrian Crouch pitched the idea of the Challenge after the school called out for novel programs. Three teachers volunteered to convert their lunchtime coding club into a solar car team.

Using accessible Sheridan kit cars – “If you can build IKEA furniture, you can do this.” – they guided Grade 4 and 5 students through a term-long program that culminated in the team winning an award for Best First-Time Entrant in 2024.

And then there are the students themselves. Alicia from Laurimar Primary, near Mernda in Melbourne’s outer north-east, was so inspired she made her own video tutorial explaining how she built her Sheridan kit car, troubleshooting wiring errors and offering tips like, “Read the instructions multiple times” and “Think about logo placement before sealing the car”. She also delivered her own environmental message: Solar technology matters.

Another 10-year-old competitor described how his team solved a capsizing problem by slanting the solar panel to improve balance and aerodynamics. More importantly, he added, they learned “how to work together and make everyone’s ideas into one”.

A culture of excitement and generosity

Competition day has all the energy of a sports carnival with a science twist. The air is full of excitement, and sometimes tension, as students scramble to repair vehicles that stop mid-race. Yet the atmosphere is remarkably cooperative. Teams lend parts to each other, judges encourage perseverance, and success is measured as much in learning as in lap times.

This culture has been part of the Challenge since the beginning. A 1995 education paper noted that while students were technically just measuring resistance or testing solar output, the excitement was “electric”. In 2003, the-then chair of the Engineers Australia’s electrical engineering branch, marvelled at seeing “a group of girls so excited by an engineering project”, when their car reached the finals.

That legacy continues. Today, girls are strongly represented at the junior levels, often leading the costume design competition that accompanies vehicle building. Participation drops somewhat at the senior end, however. Still, the Challenge consistently shows that STEM can be inclusive, hands-on, and joyful.

Why it matters

The societal benefits of the Challenge are clear. Students learn that STEM is not just theory, it is a toolkit for solving real problems. They gain knowledge of teamwork, communication, and resilience along the way. “When students understand they can do something with STEM, that is when it becomes valuable to society,” Clint says.

For some, it even sparks lifelong careers. The current vice chair of the Victorian branch of the Challenge, Imogen Forsyth, recalls starting as an “art-oriented kid” who loved hands-on creativity. Building solar boats in Grade 4 led them into mechanical engineering and, eventually, into leadership of the Challenge itself.

Looking to the future

Organisers are always exploring new ways to expand the program. Ideas include an “open” category for parents, many of whom itch to get involved, and perhaps even turning the event into a season-long league where teams compete and refine their vehicles week by week.

But at its heart, the Victorian Model Solar Vehicle Challenge will remain what it has always been: a chance for kids to discover the thrill of science by racing on sunshine.

As Clint puts it, “The real achievement is when you help a child realise that with a bit of teamwork, some problem-solving, and only the power of the sun, they can achieve something remarkable, like a car racing around a track.”

Discover how you can join the society

Join The Royal Society of Victoria. From expert panels to unique events, we're your go-to for scientific engagement. Let's create something amazing.